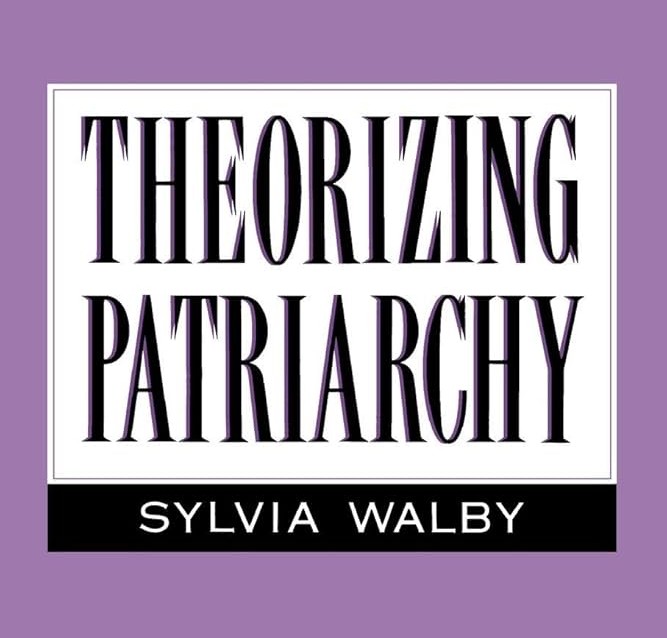

A couple of months ago I came across the article “Gendered inequalities in competitive grant funding: an overlooked dimension of gendered power relations in academia”. I enjoyed reading it and I was very much surprised by the introduction and the literature review. The article explores gender differences in scientific funding using a theoretical basis that I am not used to find in the scientometrics literature (Steinþórsdóttir et al., 2020). In particular, the authors draw on Sylvia Walby’s ideas on the segregation and subordination of women in the workplace. The book cited in the article where these ideas are developed is “Theorizing Patriarchy” from 1990, a classic in feminist literature (Walby, 1990). A desire to better understand these concepts led me to read it.

Throughout the book, Walby identifies and explores the different pillars of patriarchy, analysing in detail how different theoretical approaches have attempted to understand them. For each pillar (paid work, housework, sexuality, culture, violence and the state) we get an illustrative description of the main theories on each pillar within liberal feminism, Marxist feminism, radical feminism and dual system theory (a synthesis of radical feminism and Marxist feminism). The author ends by mentioning what are the main changes in patriarchy in recent years, according to her investigations.

In the framework of my research (gender differences in science and the impact they have on the knowledge generated) I found this book very illustrative. In this short note I want to emphasize the main learnings I draw from the reading, as well as the limitations (mostly due to the age of the text) that I have encountered. I will do this by linking certain elements of the book to my own line of research and other thoughts that I’ve had while reading this book.

Lessons.

The author knows what it’s doing. Even before the first chapter, Walby includes a reflection on how current (1990s) science reproduces the gender gap. We are no strangers to cases of 20th century and earlier scholars who have used scientific methods and the support of the academic community to show their sexist or racist biases. To reverse this trend and counteract all this sexist knowledge, the author points out two possible responses. First, existing methods in science can be used to shatter erroneous assumptions about women. What is problematic about this approach is that it assumes that there are neutral research methods and that the way in which knowledge is elaborated is neutral as well. However, this may not be the case. The second response, based on Harding’s writings, focuses on arguing that the only unbiased knowledge is women’s own direct experience, avoiding the use of scientific methods created by men. Although debatable, the emphasis on the qualitative, which allows women themselves to do the talking, without being mediated by a science that was not initially created for (or by) them, is very compelling.

Moreover, this discussion can be related to the current devaluation of the Social Sciences and Humanities: is the quantitative elevated and the qualitative relegated to the background because these are the areas where there are currently more women? In this sense, Larregue and Nielsen’s analysis focusing on Bourdieu’s hierarchies of knowledge (Larregue & Nielsen, 2023) or the “contagion of disrespect” mentioned by Wong and Rubin (Wong & Rubin, 2023) are enlightening. Both analyses reveal a devaluation of those areas where there are more women, which are, precisely, those with a more qualitative cut. Also, given the current political climate, it is worth remembering the retrograde and sexist roots of what is supposed to be the pinnacle of the neutral, the quantitative and the technological (for more information, read “Headed for technofascism: the rightwing roots of Silicon Valley”).

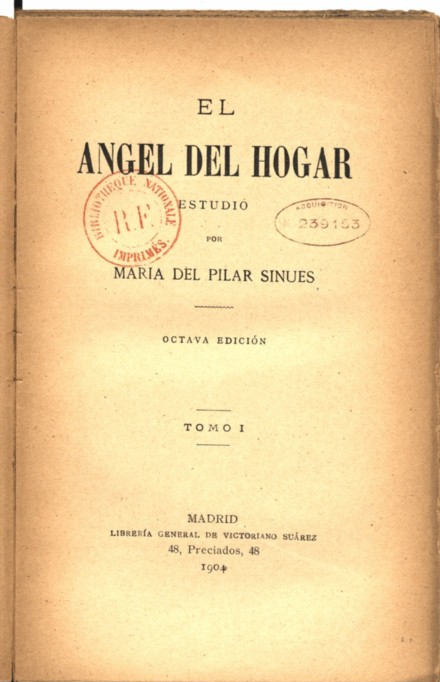

In this regard, the author discusses the extent to which technological advances in the home have served to liberate women, to stop being the “ángel del hogar”. In her review of theories on the subject, some researchers believe that reproductive technologies rescue women from their biology while other authors have argued the opposite, that is, that the development of new reproductive technology increases patriarchal power rather than diminishing it. They argue that we are witnessing a shift of power over the reproductive process from women to a medical profession controlled by men. There are also other thinkers who discuss the domestic division of labour following the inclusion of new household appliances and technologies in the home. For example, in the case of washing machines, Cowan notes that, since they have been introduced, clothes are washed more often, so that the total time spent cleaning clothes is not reduced.

The book also got me thinking that the way we do science in academia is framed by liberal thought. Just as radical feminism understands that men as a group are the major beneficiaries of women’s subordination and Marxist feminism understands that gender inequality comes from capitalism, in liberalism subordination is not understood as a result of social structures, but as the sum of many small daily deprivations. In this way, liberal thinking does not look for the roots of gender inequality, it shows its effects on certain particular elements. And this is precisely how we understand gender inequalities in science in my field of research (Scientometrics), although it is not made explicit: we focus on a particular element in which gender inequality is expressed, instead of trying to go beyond and find the roots of the social structure that legitimizes such inequalities.

Although this is legitimate given the limitations of the methodology and data, I feel that it would not be superfluous to reference this limitation in our research. In this sense, Walby’s use of “social structure” in her definition of patriarchy (a system of social structures and practices in which men dominate, oppress and exploit women) has been illuminating. The author herself stresses that “the use of the term social structure is important, as it clearly implies the rejection of both biological determinism and the notion that each individual man is in a dominant position and each woman in a subordinate one.” I was surprised at the difficulty I encountered in trying to employ this concept in an article, to the point that I opted to eliminate it. However, this book has given me the theoretical basis for not eliminating it if I need to re-emphasize the totalizing and slippery nature of patriarchy.

Because of my research topic I was particularly interested in the second chapter, which focuses on wage labour. Apart from an interesting literature review following the previously mentioned theories, Walby explains the difference Hartmann made about patriarchal strategies in employment. At the beginning of the 20th century, the strategy was one of exclusion: women were completely banned from a field of employment, such as science. Then, another type of strategy began to develop: segregation. That is, women were allowed to participate in the labour market, but women’s and men’s work was separated, and the former was classified as inferior to the latter in terms of pay and status.

In this sense, the author distinguishes between degree and form of patriarchy. Degrees of patriarchy refer to the intensity of oppression in a specific dimension; forms refer to the general type of patriarchy, defined by the specific relationships between different patriarchal structures. Some specific aspects of patriarchy are weaker than before, but progressive reforms have been met with patriarchal backlash, often on new issues rather than the same ones, says Walby. Thus, just because women are not openly banned from public spheres it does not mean that there is no exploitation and inequality there. All these ideas lead to a questioning that I had been reading for some time, about whether the concept of gender parity in science (same number of woman researchers as man researchers) is a sufficient indicator to report on the situation of women in academia. Maybe a change in degree (having more women researchers) does not mean a change in form. They also serve to question all those who express their disenchantment with gender studies and report that they are no longer needed. The shift from a strategy of exclusion to segregation undoubtedly changes the situation. But one could even say that it makes it more complex. At least more complex to measure, study and understand. This does not make it a subject that should be studied less, but much more.

Limitations.

We are dealing with a book written more than 30 years ago, a fact that does not go unnoticed. Not only does it lack a queer discussion, but her treatment of race, though present, is more of a parenthesis than a key piece of her thinking. Moreover, it focuses heavily on the UK and US, so certain elements of Walby’s main theses may not be applicable elsewhere.

It would also be interesting to read an update of the book, where one could see how what the author calls the shift from a private patriarchy (one based on domestic production, where the father/husband is the direct and individual beneficiary of women’s subordination) to a public one (women are not excluded from public spheres, but are nonetheless subordinated within them) has evolved.

Moreover, the book focuses on studying elements that may be considered less relevant today, such as the division of household chores or the role of the state in creating laws that protect women. However, I believe that the outdatedness of her data and the laws mentioned should not be a reason to eliminate all her assertions. That is, this limitation of content does not imply a limitation of form. For example, if we focus on the division of household chores, this division may not be as striking today as it was at the end of the 20th century, but it should not be ignored, nor should it be thought that it is something already overcome (since, by the way, it is not. See, for example, the case of science workers, as shown by Derrick et al. (2022)). It would only be necessary to update the type of oppression to that of the 21st century.

Conclusions.

Reading this book has been very enriching. It provides the reader with a theoretical basis that is not always present in bibliometrics and gives support to concepts that until now I only understood intuitively. It seems important to me to understand patriarchy as a social structure and its different representations as a vicious circle that affects all spheres of life and science. I understand that this makes its study more complex, because how can we study something that is everywhere? However, where there is power there is resistance and there are always cracks where we can investigate further. Always bearing in mind, of course, that a lack of evidence in the data does not imply that we do not live in a patriarchy. Perhaps it has more to do with the fact that we are not looking where we should.

Lastly, because of the somewhat “meta” nature of my research, this book has been like putting a mirror in front of me. What science do we want to do? How do we want to investigate the gender gap in academia? Is parity enough to measure it, or should we go further? How can we study something as elusive and yet as evident as patriarchy? I believe that in theory we can find many avenues to guide our research, and, through this small note, I advocate for a greater presence of it in our science. Data are all very well, but they don’t speak if we don’t ask them the right questions or frame them in something bigger.

References

Derrick, G. E., Chen, P.-Y., van Leeuwen, T., Larivière, V., & Sugimoto, C. R. (2022). The relationship between parenting engagement and academic performance. Scientific Reports, 12(1), 22300. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-022-26258-z

Larregue, J., & Nielsen, M. W. (2023). Knowledge Hierarchies and Gender Disparities in Social Science Funding. Sociology, 00380385231163071. https://doi.org/10.1177/00380385231163071

Lewis, B. (2025, 1 febrero). “Hacia el tecnofascismo”: las raíces reaccionarias de Silicon Valley. ElDiario.es. https://www.eldiario.es/internacional/theguardian/tecnofascismo-raices-reaccionarias-silicon-valley_129_12009236.html

Steinþórsdóttir, F. S., Einarsdóttir, Þ., Pétursdóttir, G. M., & Himmelweit, S. (2020). Gendered inequalities in competitive grant funding: An overlooked dimension of gendered power relations in academia. Higher Education Research & Development, 39(2), 362–375. https://doi.org/10.1080/07294360.2019.1666257

Walby, Sylvia (1990). Theorizing patriarchy. Oxford: Blackwell.

Wong, K., & Rubin, H. (2023). Social Dynamics and the Evolution of Disciplines. Philosophy of Science, 1–10. https://doi.org/10.1017/psa.2023.149